A selection of our current exhibits

- St. Anne from Cologne

St. Anne from Cologne

St. Anne from CologneThe third sculpture of St. Anne with the Virgin and Child on display at the Mining and Gothic Museum in Leogang is on private loan and comes from the Cologne workshop of the master craftsman Tilman. Tilman appears in the archives as having been in Cologne between 1487 and 1515 and is the most important sculptor and woodcarver of Cologne’s Late Gothic Period.

Originally, the group of figures probably stood in the centre of a small winged altarpiece. They are carved in oak, are flat at the back and were made between 1500 and 1510.

Mary’s high forehead and fine, open, wavy hair below a simple crown are typical of sculptures from Tilman’s workshop.

- Georgius Agricola12 books on mining

Georgius Agricola12 books on mining

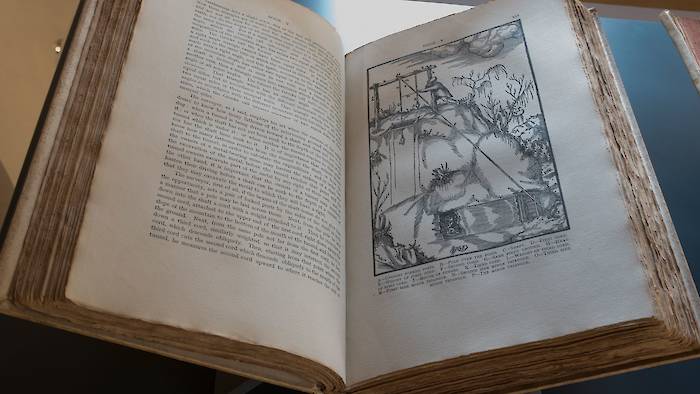

Georgius Agricola12 books on miningGeorgius Agricola (Latin for ‘Georg Bauer’) was a German doctor, pharmacist and scientist who is regarded as the ‘father of minerology’ and founder of modern geology and mining engineering. His main work De re metallica libri XII, ‘12 books on mining’, appeared for the first time in Latin in 1556, a year after his death, in Basel.

Agricola’s work is the result of his travels through the mining regions of the Saxon and Bohemian Ore Mountains and demonstrates a systematic, technological investigation of mining and trade associations. Decorated with woodcuts, the entire mining knowledge of the day was compiled by the author, who in doing so became the founder of mountain scholarship. For two hundred years, Agricola’s books remained the decisive work on the subject.

Later, the famous mining book was translated into many different languages. Philippus Bechius (1521-1560), a friend of Agricola and a professor at the University of Basel, translated the manuscript into German and published it in 1557 under the title Vom Bergkwerck XII Bücher.

The cabinet of mountain curiosities at the Leogang Mining and Gothic Museum has three different editions of the famous work on display: the second Latin edition from 1561, the second German edition from 1580 and the first English edition from 1912, also called De re metallica.

The first English translation was published by Herbert Clark and Lou Henry Hoover, a married couple, who added commentary and footnotes. Herbert Clark Hoover was not only a trained mining engineer and successful entrepreneur, but the 31st president of the United States of America from 1929 to 1933.

The three editions of Georgius Agricola’s work on show at the Mining and Gothic Museum come from Achim and Beate Middelschulte’s famous private collection of mountain art in Essen.

- Processional silver crossThe hallmarks’ message

Processional silver crossThe hallmarks’ message

Processional silver crossThe hallmarks’ messageThe cross shown here is silver with hallmarks from 1805 or 1809. Stamp marks on metalwork objects usually certified their precious metal content. Further stamps had to do with legal stipulations.

The cross has an eight-piece foot with a double hallmark in the rhombus containing a large ‘C’s and another with an ‘8’, denoting 8-Lot silver. In addition, there is a stamp with crossed keys. At the foot of the cross is an inscription: ‘1470’ in Gothic numerals.

On the front of the cross, the ends of the top half branch out into trefoils. Trefoils are a common element of the late Romanesque and Gothic style and consist of three, outward-pointing circular arcs with the same radii as inscribed in a circle.

Left and right can be found the single letters ‘F’ and ‘H’ (probably the owner’s initials). At the top is the inscription ‘IH. CROS’, the abbreviation for ‘Jesus Christ’. The inscription ‘INRI’ (‘Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews’) can be found above a relic window in the shape of a Teutonic Order cross. The trefoil on the lower end is decorated with a black, wolf-like animal in a blazon. The ring at the top end once served to attach a securing tape to ensure the cross did not fall during prayer processions.

The reverse shows an engraving of St. Christopher with the Infant Jesus and has a removable piece of the True Cross under clear quartz along with the coat of arms of an unknown bishop.

The inscription ‘receptacle containing the confirmation from Rome of the authenticity of this piece of the True Cross’ can be found on the bottom plate. This was the certificate of authenticity of a relic issued by a bishop. The foot of the cross is hollow, presumably it once held the now-lost certificate. The processional cross comes from the Margarete Sperl collection. It was a gift from His Magnificence Günther Georg Bauer, privy councillor of Salzburg.

Our Museum Audio Guide

Interested in our exhibits?

Our free media guide provides fascinating information.

Have a look: Audio-Guide