A selection of our current exhibits

ibex horn bowl

Art in a natural material

The horn of the alpine ibex was processed from the second half of the 17th century on. The material…

Emeralds from Habachtal

Glittering jewel

The emerald source in the Habachtal valley, at Bramberg in Oberpinzgau, is the only significant…

Cast copper cake

Historical find

It is thanks to a fortunate coincidence that the Mining and Gothic Museum is in possession of a…

St. Anne from Cologne

The third sculpture of St. Anne with the Virgin and Child on display at the Mining and Gothic…

Pannier carriers by Simon Troger

Pinnacle of Baroque mountain art

The so-called hand stones represent the pinnacle of Baroque and Late Baroque mountain art. Hand…

Herrengrund receptacles - Rare treasures

Rare treasures

Several of the famous Herrengrund copper receptacles are on show in the cabinet of mountain…

Processional silver cross

The hallmarks’ message

The cross shown here is silver with hallmarks from 1805 or 1809. Stamp marks on metalwork objects…

Winged altarpiece from the Frey collection

Largest Gothic collection in Salzburg

A particularly valuable exhibit from the Gothic Room of the Mining and Gothic Museum in Leogang is…

Lion Madonna

Rare masterpiece

Madonnas standing or enthroned upon a lion are very rare. The first of these sculptures probably…

Screw-medal from Abraham Remshard

Augsburg masterpiece

The silver screw-medal at the Mining and Gothic Museum dedicated to the Salzburg émigrés of 1731…

Portraits of Salzburg exiles

Two portraits in typical folk costume

The march of the 1731 and 1732 émigrés from Salzburg to East Prussia caused a great stir among the…

Coins from Leogang silver

Sought-after collectors’ items

The quality of the silver from the mines in medieval Leogang was excellent and it was used for…

Cobalt and cobalt blue glass

The colour blue in art and applied art

From the beginning of the 16th century until the end of the 18th century, Leogang was famous…

Gezäh and lighting

Tools and light

A miner’s toolset was known as ‘Gezäh’ (Old High German for ‘gizawa’, meaning ‘succeed’). This was…

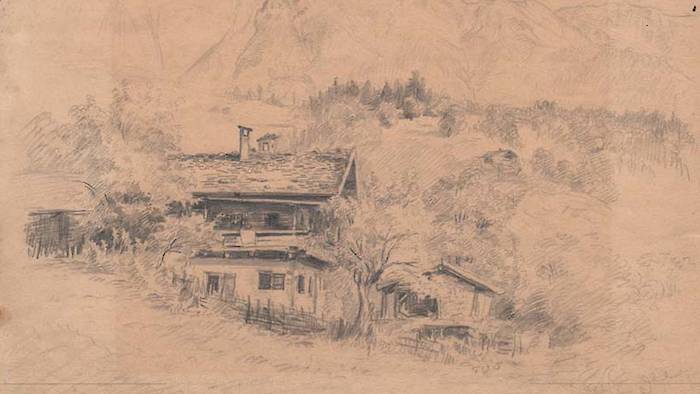

Painting of Grundbach

Growth of building culture

Very close to where mining administrator, tourism pioneer and painter Michael Hofer worked lies the…

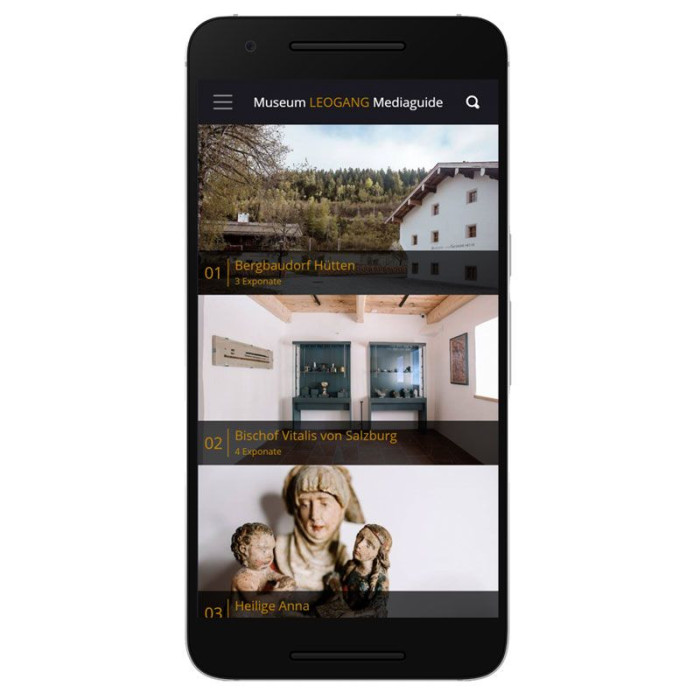

Our Museum Audio Guide

Interested in our exhibits?