Ein Auswahl unserer aktuellen Exponate

- Buttenträger von Simon TrogerHöhepunkte barocker Bergmannskunst

Buttenträger von Simon TrogerHöhepunkte barocker Bergmannskunst

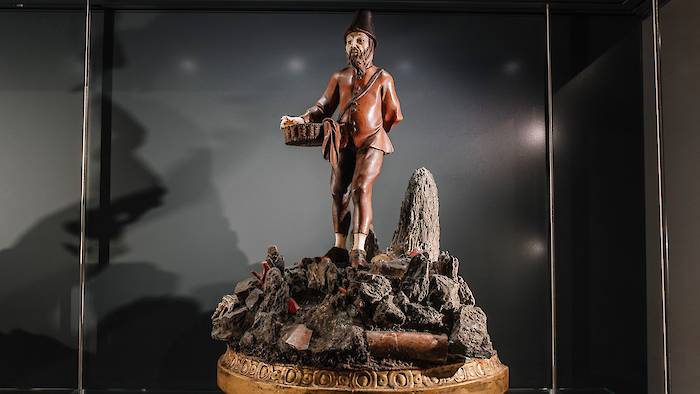

Buttenträger von Simon TrogerHöhepunkte barocker BergmannskunstDie sogenannten Handsteine gelten als Höhepunkte barocker und spätbarocker Bergmannskunst. Handsteine sind besonders schön kristallisierte Mineral- oder Erzstufen, die unter Einbringung von Motiven aus dem bergmännischen Alltag künstlerisch bearbeitet und auf kostbaren Sockeln ausgestellt wurden. Von diesen seltenen Zeugnissen der Bergbaukunst ist weltweit kaum mehr als ein Dutzend erhalten.

Die bergmännische Schatz- und Wunderkammer im Bergbau- und Gotikmuseum Leogang präsentiert zwei Handsteine mit darauf angebrachten Figuren, sogenannten Buttenträgern, gefertigt im späten 18. Jahrhundert in der Tiroler Werkstatt von Simon Troger.

Zunächst eine große schreitende Figur mit Hut, das Gesicht aus Elfenbein oder Bein, also Knochen, gearbeitet, die auf einem aus Mineralien und Gesteinen zusammengesetzten Hügel angebracht ist. Zu erkennen sind Rauchquarz, Glimmerschiefer, Aktinolith (aus dem Griechischen für „Strahlstein“), aber auch ein kleines Amethyststück, polierte Karneole, Schnecken und Korallen. Der Handstein samt Figur sitzt auf einem vergoldeteten, aus Holz gefertigen, geschwungenen Sockel.

Ganz ähnlich der zweite Handstein aus der Werkstatt des Tiroler Meisters Simon Troger: auf einem aus Holz halbkreisförmig geschnitzten und vergoldeten Sockel ist ein aus Mineralien und Gesteinen zusammengefügter Hügel aufgebracht. Auch hier sind Rauchquarz, Marmorstückchen, ein sehr charakteristischer, spitz zulaufender Aktinolith, aber auch kleine polierte Karneole, Korallen und Muscheln zu erkennen. Darauf eine große Figur mit hohem Hut, Gesicht und Hände aus Elfenbein oder Bein, also Knochen, gefertigt.

Beide Handsteine mit Figuren sind Leihgaben des Bankhauses Spängler in Salzburg.

- Herrengrunder Gefäße

Herrengrunder Gefäße

Herrengrunder GefäßeGefertigt aus sogenanntem Zementkupfer, einem Zwischenprodukt bei der Gewinnung von Kupfer aus kupferarmen Erzen, wurden diese seltenen Kostbarkeiten nach dem Ort Špania Dolina, zu Deutsch Herrengrund, wenige Kilometer nördlich von Banská Bystrica im slowakischen Erzgebirge, benannt.

Hier entdeckte man im lokalen Kupferbergwerk 1605 eher zufällig den Vorgang der Zementation: werden Eisenstücke in Kupfersulfat-reiche Bergwässer gelegt, fällt durch Ionenaustausch elementares Kupfer aus. Man hielt das damals für ein Wunder und das dabei entstandene Zementkupfer wurde von Silber- und Kupferschmieden der Region zu allerlei Gefäßen verarbeitet, die anschließend feuervergoldet, zumeist mit eingravierten Sprüchen versehen und manchmal mit kleinen silbernen Bergbausymbolen ausgestattet wurden.

Die Herrengrunder Sprüche sind meist in deutscher Sprache verfasst, seltener in lateinischer und slawischer Sprache. Sie beziehen sich häufig auf die Entstehung des Kupfers oder auf die Trinkgewohnheiten der Bergleute und zeugen von dessen authentischen Humor. Meist sind die Sprüche in Reimform verfasst, das Hauptmotiv dabei lautet: „Eisen war ich, Kupfer bin ich, Silber trag ich, Gold bedeckt mich“.

- Kobalt und kobaltblaues GlasDie Farbe Blau in Kunst und angewandter Kunst

Kobalt und kobaltblaues GlasDie Farbe Blau in Kunst und angewandter Kunst

Kobalt und kobaltblaues GlasDie Farbe Blau in Kunst und angewandter KunstVon Anfang des 16. bis zum Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts war Leogang wegen seines Reichtums an Kobalt- und Nickelerzen in ganz Europa berühmt.

Den Kobalterzen kam hier ab Mitte des 16. Jahrhundert eine besondere Bedeutung zu: in sogenannten Blaufarbenwerken wurde durch Erhitzen der Kobalterze zunächst Zaffer, auch Safflor oder Kobaltsafflor genannt, erzeugt. Zaffer wiederum diente als Grundstoff für die Herstellung von Smalte, einem blauen, pulverartigen Glaspigment. Da sowohl Zaffer als auch Smalte feuerfest waren, wurden die Stoffe zur Blaufärbung von Glas, Porzellan und Keramik, aber auch in Ölfarben verwendet.

Besonders gefärbtes Glas aus Venedig galt in den deutschsprachigen Ländern Europas ab Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts als besonderes Luxusgut. Deutsche Handelsherren, wie die Welser und die Fugger, hatten bereits um 1225 in Venedig das Fondaco dei Tedeschi gegründet, zu Deutsch etwa „Der Lagerraum der Deutschen“. Das am Canale Grande direkt neben der berühmten Rialtobrücke gelegene Gebäude wurde zum Umschlagplatz der aus Venedig in die deutschsprachigen Länder exportierten Luxusgüter.

Da man zur Blaufärbung des Glases in Venedig vermehrt Zaffer und Smalte verwendete, wurde Kobalt aus den Salzburger Lagerstätten ab Mitte des 16. Jahrhunderts zum unverzichtbaren Rohmaterial für venezianisches Luxusglas.

Der Hinweis auf den Abbau und die Verwendung für Glas findet sich etwa in Georg Agricolas „De re metallica Libri XII“ (1556). Jenem Meisterwerk der Bergbauliteratur, das ebenfalls im Bergbau- und Gotikmuseum Leogang zu bewundern ist.

Die Farbe Blau erlebte auch in der Malerei einen ungeahnten Aufschwung. Bereits ab dem 12. Jahrhundert erhielt die zunächst dunkle und glanzlose Farbe als Symbol für den Himmel und die Jungfräulichkeit der Muttergottes neue Bedeutung. Glasmacher und Buchmaler bemühten sich, dieses neue Blau mit der veränderten Lichtauffassung, die die kirchlichen Bauherren von den Theologen übernahmen, in Einklang zu bringen. Die Strahlkraft kobaltblau gefärbter Ölfarbe verschaffte den bildenden Künstlern der frühen Neuzeit ganz neue Möglichkeiten.

Heute kommt Smalte, das kobaltblau gefärbte Glaspulver, vor allem bei der Restauration alter Meisterwerke zum Einsatz.

Unser Museum Audio Guide

Informationen zu allen unseren Exponaten?

In unserem öffentlich verfügbarem Museum´s Audio-Guide können Sie durch unsere Räume und Exponate stöbern.